Wednesday, November 18, 2020

MONMOUTH, Ore. – On that morning in early June, Curtis Anderson couldn’t contain his emotions.

Anderson called his mother and just started yelling. Normally an even-tempered person, the emotions that morning were raw and racing. Like water through a breached dam, he couldn’t hold back.

“I was so angry and she was so confused,” Anderson said. “I was just freaking out and yelling, ‘Screw that town. Why are people doing this?’ She is my mom and she was trying to calm me down. For me, I just wanted to be heard and I let everything fly.”

The flashpoint for Anderson was an online feature published by NBC News detailing a Black Lives Matter protest in his hometown of Klamath Falls, Oregon, a rural farming city in the south-central part of the state along the California border.

A group of 200 people, a cross-section of the community, arrived at Sugarman’s Corner in support of Black Lives Matter and protesting the May death of George Floyd in Minneapolis. Across the street, a counter-protest emerged. People armed with baseball bats, axes and guns turned out in the hundreds. Fueled by online posts later found to be baseless, counter-protesters claimed that busloads of antifa members were coming to town to cause trouble.

For Anderson, whose mother is white and biological father is African American, the events of May 31 were extremely personal. This was not the Klamath Falls that he grew up in, the one that celebrated him as an all-state football and basketball player at Mazama High School.

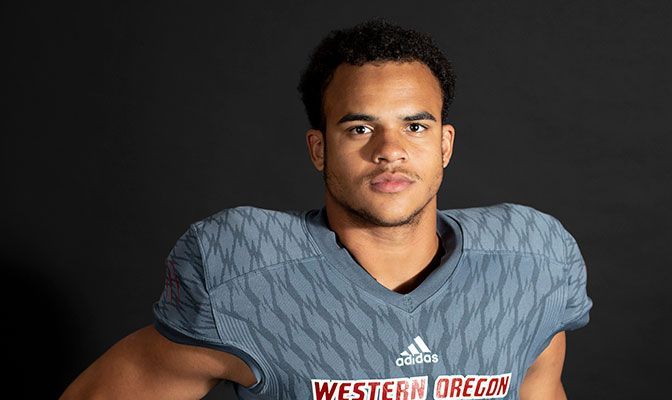

“I read the article and I broke down. I started crying. I was so angry,” said Anderson, who is now a senior All-GNAC defensive back and return specialist at Western Oregon University. “It made me sad because I was not able to step back and see how political it had become so quickly. I just thought we could step in front of the politics for the sake of racial equity.”

The article opened a raw nerve in Anderson, who has come to terms with his perceptions about race, racial justice and equity since arriving at Western Oregon in 2016. The way he dealt with those issues was not the way his teammates dealt with them. His experiences were far from those of his teammates who grew up around sharper racial divides.

A BLACK YOUTH IN THE BASIN

Even as a biracial child raised by a prominent white farming family, Curtis Anderson was Black in the Klamath Basin. According to government Census numbers, over 88 percent of Klamath County’s population identifies as white. Just over four percent identify as biracial and less than one percent identify as Black.

Anderson spent his early years in Dorris, California, a small farming town of 1,000 people located 20 miles south of Klamath Falls. He remembers being rallied around in Dorris, simply because it was the kind of town where everyone was related to everyone else.

It was when his family moved to Klamath Falls when he was in the fifth grade that Anderson recalls his first experience with racism. It was 2008 and Barack Obama had just been elected president of the United States. He was sitting on a swing and had a little girl run his way. She told Anderson that her father had told her that Obama would be assassinated because he was a n-----.

It was far from the last time Anderson would face racist jabs. Shut up, brown boy. Shut up, monkey. And worse.

But rather than be offended by the words, Anderson’s coping technique was to deflect, to talk as much trash as he was given. He developed a thick skin and a quick wit. The best way to deal with racism, he believed, was to not give it much attention at all.

“I just made it so small. How can you hurt me if that word means nothing to me,” Anderson said. “If calling me the N-word, calling me a monkey, making fun of my hair, if it means nothing to me and I can say it loudly as a joke, how can you hurt me with it? For me, personally, it worked. When you’re 15, if you call a kid an insult and he just laughs it off, you’d probably stop. So I made racism very small and make a joke of it. And that’s how I felt I overcame it.”

But while Anderson deflected those types of comments, others took them much more seriously. He recalls an incident on a bus ride home from school where his sister, Hayley, was the target of a racial comment from another girl. Curtis didn’t hear what was said but it was clear that whatever it was shook Hayley.

The next morning, Anderson’s mother, Melissa, informed both kids that they would not be going to school that day. While Curtis spent the day at home playing Xbox, Melissa took to the task of defending her children.

“The next day that I was at school, people were giving me that funny look when everyone knows something that you don’t,” Anderson recalls. “So I asked my best friend what was going on and he said, ‘Bro, your mom is crazy.’ It turns out that morning my mom had waited for the bus, got on the bus and confronted this girl about how she was being racist to her daughter. She just went off on this girl.”

But for every insult that Anderson has endured, he has just as many stories about the people who have mentored him, nurtured him and loved him in Klamath Falls and have helped him succeed in life.

“The majority of people that were around me weren’t bad,” Anderson said. “I had relationships and opportunities afforded to me with people in that community who put me where I am at. It gave me the opportunity to go to school. It gave me the opportunity to pursue a career in what I love. The majority of people aren’t bad at all. I don’t believe that for a second.”

Those that mentored, nurtured and loved Anderson saw him blossom at Mazama. An all-state selection in both football (a two-way honoree at quarterback and defensive back) and basketball, Anderson was named both the Skyline Conference’s Football and Boys’ Basketball Player of the Year as a senior. It marked just the third time in Klamath Basin history that one athlete had been named a conference player of the year in two sports in the same year.

That athletic ability landed Anderson a scholarship to Western Oregon where he learned that his views on race differed greatly from those who would become his teammates.

CHANGING PERSPECTIVE

In Klamath Falls, Curtis Anderson was a Black man. When he arrived at Western Oregon University, the question of race was not as easily answered.

“I’m a mixed kid from a farm town so I am hardly Black to some of my teammates,” Anderson said. “They kind of looked at me as if I was Black in name only. When I got here, I realized that my identity was so far detached from the color of your skin.”

While Anderson was certainly the subject of racial jokes and insults in Klamath Falls, he learned that those experiences were nothing compared to what some of his teammates experienced in their hometowns like Sacramento, Oakland and Stockton. Where Anderson believes innately in the good in people, he quickly learned that others saw life from a much different perspective.

“I had to grow when I came to Western,” Anderson said. “People from inner-Sacramento and Oakland, kids who were Black who had been through things and experiences that would make them have a disdain for police officers, that would make them have a disdain for white people. I had to meet them to understand their perspective, just like they had to meet me to relieve the Uncle Tom label or to feel like I wasn’t Black enough to fit in with them.”

Anderson listened and learned about those experiences. By his sophomore year, Anderson shared an apartment with roommates who were Muslim, Irish and Hispanic. In his junior year, he was asked to host a prospective African American player for a campus visit and was shocked to learn that the kid’s parents believed that he if spent another month in his hometown, he could be shot.

But it wasn’t until the race-fueled protests in 2020 and the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery and other African American men and women that Anderson’s lighter approach to racism became more serious.

“It sounds weird because I am Black, but it was a real ‘think about it’ moment for me because I realized that some people can’t afford to make it small,” Anderson said. “In the case where you feel like a cop is profiling you, you can’t afford to make it small and make a joke. In a case where you don’t get a job because of the color of your skin, there is no use making a joke.

“It was seeing how much pain some of my teammates were in and seeing how hurt the country was that made me evaluate how I handled racism and how light-hearted I had become about something that was very serious and was a real issue for some people.”

That awakening is something that Anderson directly credits to his involvement in college football. While 2020’s tensions shined the spotlight on race, he firmly believes that being part of football’s diverse environment provided a significant and unique learning experience.

“Football is a true melting pot,” Anderson said. “The true symbiotic relationship you have with all of these different races, all of these different religions, all of these people from every socioeconomic background. I don’t know if there is another thing on the planet that gives you that experience.”

Even with that realization, Anderson still brings an important perspective of his own to the discussion on racism and race relations. Being biracial, he knows first hand that there is more to the conversation than the extremes. The conversation is more gray than it is black and white.

WHAT YOU TOLERATE, YOU ENCOURAGE

Curtis Anderson loves Klamath Falls. Like many children who grow up in small towns, the community provided opportunities that would not be available in larger cities no matter what your ethnic background.

“That place sculpted and shaped who I am,” Anderson said. “I don’t know who I would be without Klamath Falls. It’s my hometown and I am grateful for all of my experiences there and all of the people I have encountered there, good and bad.”

That’s what made the descriptions by NBC News of the May 31 protests and the reactions on social media from people that he knows and respects hurt so much. To him, it was personal. It was wrong.

“I was on Facebook and seeing things from people who grew up calling your games or working the concession stands, all of these people who are close to you as you grew up and you see them saying, ‘What did you expect us to do?’ It became political immediately. It became polarizing immediately,” Anderson said. “I knew people there and more grossly I saw even more of the comments afterward.”

Anderson carries with him a mantra that his high school football coach, Vic Lease, preaches to his players: What you tolerate, you encourage. It’s a lesson that carries meaning well off the football field and into every aspect of his life.

It’s a mantra that Anderson believes is pertinent to not only his hometown but to every small, rural city struggling with diversity and race relations. It’s not enough to be good but you have to speak up, you have to act when it’s not right.

“Don’t encourage racism, don’t encourage tolerance,” Anderson said. “If you hear someone say something that is stupid or doesn’t make any sense, that’s wrong about any race or police or anything else, speak up. I pride myself on having learned that lesson there.”

Even with his changed view on dealing with racism, Anderson said that he will never be someone who champions race politics and the polarization of race relations. He still believes that most people are good at their core. He believes that people have a lot more in common than they ever will have that draws them apart.

Curtis Anderson experienced that good within his family. He experienced that good with the families, friends and mentors that surrounded him growing up. He experiences that now with the football family that he is part of at Western Oregon. Everyone is different but it is those differences that make everyone stronger.

And to experience that common good, whether in Klamath Falls or anywhere else, it takes stepping up and speaking up when things aren’t right.

“I have a resounding and unending love for that town. And I want them to know that what they tolerate, they encourage,” Anderson said. “If you’re someone that people have respect for, regardless of what your political opinion is, regardless of what you feel your experience is, say something. If someone is uncomfortable, if someone feels marginalized, if someone is feeling left out, be the love.

“Be the person to say something.”